This article centres on the experience of two naval officers serving on the Australia Station. It gives us an insight into the work of the Station in the later Victorian era. Captain Clayton wrote to his wife every day telling her of the day’s events and Lieutenant Marx kept up an intermittent Journal. It is taken from a paper presented to the Maritime History Conference, University of Exeter, September 2007.

Dr. Mary Jones January 4th, 2008

Captain Francis Starkie Clayton was forty seven years old when he arrived on the Australia Station and took up command of HMS Diamond in January of 1885. His wife of four years had already presented him with one son and the birth of his second child was immanent. He wrote to his wife every day and viewed a long commission on the Australia Sation with misgiving and frustration tempered by Victorian resignation to duty.

The 31 year old Lieutenant John Locke Marx saw it quite differently. He was delighted at the appointment. He might still only be a Lieutenant but now he would be a Lieutenant and the commanding officer of his own ship. He wrote eagerly, ‘Hoisted my [underlined twice] pendant. What a rum thing to do!’ and gleefully took his gunboat Swinger from Plymouth to the Australia Station in the autumn of 1883.

HMS Swinger (Details of HMS Swinger and the other ships on the Australia station are in appendices at the end of the article)

HMS Swinger (Details of HMS Swinger and the other ships on the Australia station are in appendices at the end of the article)

A word about the Station in general: It was founded in 1859, in the words of an Admiralty order, ‘to protect British interests in the Colonies….to give the natives an impression of the power and the friendly disposition of the British nation, whilst giving due weight to the representatives of the British consuls and missionaries..’.1 By 1885, as you will see from your map, it stretched from the Antarctic circle to the Marshall islands and from Cocos Islands to the Cook islands. Before 1885 the British Government had taken little interest in it. It was too far away and too expensive. But, by 1885, the threat of outside invasion and other predatory foreign interests in the area had forced the British government to rethink its attitude. The ‘scramble for the Pacific’ was hotting up. The Russian fleet was building up at Vladivostock, the French were expanding their interests in New Caledonia and the New Hebrides, the Germans were flexing their imperial muscles in Samoa, and the USA was taking an increasingly active interest in the Pacific islands. With the advent of the Telegraph in 1884, the station could be centrally run from Admiralty, so in 1885, it was up-graded to Admiral status. The impressive Rear Admiral George Tryon took over and the number of ships was increased to eleven. Not a strong force with which to keep the Pax Britannica: to guard the extensive mainland coast, protect trade, police the islands, keep the Russians at bay, and deter the French, Germans and Americans from annexing islands which although the British government did not want, it did not look favourably on any else trying to take them. Nor were the ships themselves impressive. Tryon was not impressed. He thought them ‘antiquated wooden craft much in need of extensive repair’, a view echoed by Marx and Clayton. ‘My cabin leaks lamentably so does the old ship herself’ said Clayton.

One of the problems for Captains working on the Australia Station was that of legal jurisdiction. In 1877 the High Commission of the Western Pacific2, operating out of Fiji, had made the Australia Station ·a centre from which law and order might be diffused throughout the unannexed islands of the Pacific·. It meant that offences committed in British islands were to be dealt with by commanding officers in the same manner as if they were committed on the high seas. This allowed naval captains to use their own judgement in the application of imperial law where there was no access to a civil court. But subsequent rivalry between the powers of colonial governors and naval captains led to confusion over the exact legal status of captains in relation to the civil administration. The High Commissioner was jealous of his civil powers but when naval officers and respectable white men were killed by natives, captains wanted to be able to execute summary justice without recourse to a civil court. So in 1881 it was decided to give selected naval captains the legal status of Deputy Commissioner3 but this lessened the autonomy and powers of a commanding officer without that authority. The work of Marx and Clayton illustrates these difficulties in practice.

Marx’s first task in 1884, after an anxious initial inspection which went very well, ‘The Swinger has a fine looking Ship’s Company. The men were very clean and well dressed and drilled with much spirit… (He had brought Swinger all the way from Plymouth to England) was to police the local labour trade and make sure there was no blackbirding (This was the illegal employment of natives, by abduction or fraud). Patrolling the islands, on the lookout for these illegal traders, it did not take him long to be involved in a major incident. He was cruising to the East of New Guinea, carefully looking out for reefs, when he saw a suspicious steamer, the Forest King. On sight of Swinger, she turned away. After a difficult chase Marx managed to overhaul her and sent Mr.Millman the civil Magistrate, who happenened to be on board, to investigate. It seemed that the sixty natives in the ship had been illegally obtained. Marx had the Captain of the Forest King on board and told him that he would be taken into port next day to face charges and that if he tried to get away in the night, he would sink him.

Thoroughly tired out after a day at the masthead conning the ship and half a night spent in filling in the necessary legal forms, Marx had,

‘hardly been in bed for what I thought was five minutes when the Quarter-Master came running down and reported that they were throwing coca-nuts overboard from the Forest King. I came up with my binoculars and saw that it was men they were throwing overboard. There was no land for them to swim to. They would simply be drowned or eaten by sharks, so I called away the boats and the men went away in their jumpers, not having time to put their trousers on and proceeded to rescue these men. We picked up seventeen or eighteen but more than half the forty men were missing in the morning.

The next morning Marx sent Sub Lt. Bruce and four men to take charge of the labour vessel, provided with ‘pistols, handcuffs and irons in case of necessity.’ By dint of throwing all the alcohol overboard, Sub Lt Bruce took the Forest King safely to Brisbane. Marx also had to return to Brisbane to be available for a Vice Admiralty Court of Inquiry. Not everyone was pleased with what he had done. The vested interests of the traders were threatened and feeling ran high against him in Brisbane. The Chief of Police warned him not to go into the main streets in his uniform. He had to take a back street to get to the Court.The trial took three days. An important local barrister stood for the defendants. Marx was anxious, The trial was a troublesome affair ..I thought at one time it was going against me but nil desperandum we pulled through in the end. The young Lieutenant was exonerated. He had the satisfaction of receiving a letter from Commodore Erskine.

You were not only justified in the course you pursued, but it would have been a failure of duty had you not sent that Vessel before the Vice Admiralty Court for adjudication.

Clayton’s first task when he arrived on the station in 1885, stemmed from the concern about possible war with Russia. Diamond was sent to Albany to protect the harbour. Clayton thought it futile. ‘We can catch nothing·no use expecting 10 knot ships to catch 15 knot ships’. But after three and a half months in Albany, things quietened down and Clayton received his first island patrol orders- ‘appalling orders ·8 murder cases, 1 piracy, 2 missing ships to inquire about….I shall have white hair, I expect, what with coral reefs and worries about natives and blackguard white men. He was glad the Admiral was ‘strongly averse to the indiscriminate shooting of the natives…’on the other hand when they have to be punished, what else can you do?’

In fact, Admiral Tryon was progressive in his views on the natives. He told Admiralty, ‘natives do not value life as we do.. many are cannibals, that they kill men on certain state occasions,such as the launching of a canoe, or because of the non return of natives…. they are to be won by fairness and consideration’.4 Accordingly, Clayton’s orders were ‘to let the natives know that a Naval Officer is their best friend and at the same time to punish them·..’ difficult to combine the two, I fear,’ said Clayton as he set off for New Guinea and the Solomons with the gunboat, Dart, and the schooner Harrier to catch two murderers.

The patrol started well. Dart signalled that she had the first murderer. Clayton captured a few canoes from the village concerned as a deterrent, and hoped to talk to the chief about it. If he could not get the other murderer given up, he thought ‘there might be the disagreeable alternative of destroying some of the villages·.not much use·but something must be done to stop this epidemic of murder·. Next day, a native trading alongside Diamond was recognised as the other murderer and taken on board. Clayton would not allow him to be shot, since he had given himself up thinking that ‘a trifling present would be all that was wanted. ‘If he had been taken fighting it would have been another thing but in cold blood I would not do it. ·the man shall be taken to Port Moresby and imprisoned.’ Clayton was becoming increasingly disillusioned. ‘I don’t like this dirty work at all·the price of blood comes to about 2 shillings in shell ornaments. They are all cannibals..some of our prisoner’s ornaments are bits of human bones.’

Although willing to take the prisoner to civil court, Clayton, as a senior officer was quite clear in his own mind that he had the naval authority of summary execution.

Negotiations next day failed and Clayton left, after burning three villages. He went to a local village and demanded the head of the murdered white man. They put ‘the ghastly trophy’ in a box and read the burial service over it aboard Diamond, before giving it solemn burial at sea. In desperation, since some of the natives refused to come out of their village on top of the hill, Clayton pitched a few shells into them to show that ‘even at the top of the hill they are not safe…’.But he was increasingly aware of the uselessness of this coercive treatment. No sooner were the natives aware of the approach of a man of war than they ran into the bush to hide.

The troubles continued: an old man, Childers, a local naturalist exploring an island was murdered. Tryon blamed his foolhardiness but Clayton was angered and shocked by this latest evidence of native treachery – the murder of a respectable white man. His sympathy with the natives disappeared. He burned a couple of villages where he found Childers’ possessions and cut down trees as a punishment to natives who would not yield up the murderer. He found the work increasingly disagreeable. ‘If I only had enough to live on I might retire with a clear conscience and feel I had done my duty to my country’. To add to his troubles, as his first tour of the islands finished, Diamond was running out of provisions, ‘Only one sheep left now and a few fowl.’

Dealing with the natives continued to be the main stay of work for Marx and Clayton during 1885 and 1886. In 1886 Clayton was made Deputy Commissioner.

I was in hopes the Admiral would not issue the commission for me. It is in my humble opinion a very great mistake. When you have none, you settle all the disputes by common sense · now you have to go through long forms and take evidence on oath and can only sentence to fines at the end of it which you can’t inforce [sic] – the whole thing is an absurd farce done to save money. The intention was to have several civil officers to go about in a small steamer administering justice but for economy’s sake they never bought the steamer and did not have travelling commissioners, Then some clever man suggested that Captains of men of war should do the work and the far seeing treasury jumped at it as they pay us nothing. They don’t even allow stationary or extra pay to the clerk. However, after many sheets of paper expended and much trouble, I have wrung 2/6 a day for the clerk and got 2/- for stationery for last year and will try to knock a little more out of them yet. Plus ca change.

The work continued. Islands were fortuitously annexed where possible.

This small, unidentified island is an old volcano … the flag staff … was soon erected, My proclamation in the name of the Queen, in a strong glass case, screwed on to the staff. Another one put in a bottle and buried. Then the Union Jack was hoisted and we off caps while I read the document and another bit of Great Britain was taken formal possession of. If there had been any inhabitants we should have fired a royal salute but there were none.5

‘A ‘magnificent harbour’ was discovered and all boats sent out to chart it, having no general native name. Captain Clayton named it Port Diamond.

These island patrols were always potentially dangerous. A major incident in 1886 was the occasion on which Marx was attacked at St. Agnau. After he had traded with some natives alongside Swinger one morning, and thought them friendly, he decided to land, taking the usual precautions of a covering boat. He described what happened,

On shore I met one of the natives who had been on board during the morning, to whom I made a present, the other natives were very shy but I distributed some tobacco amongst them through the medium of the same man. After about 10 minutes when I was within 10 yards of the boat and there being three of our party on shore close to me I handed him some more tobacco for things he had brought down. As he took it with one hand, he struck me over the head and right hand with a large trade knife he had in the other and jumped into the bush. Dr.McKinlay who was close to me fired at once at him but without result.

A large number of men with arms were seen hiding behind a rock at the same time I think his premature action spoiled a plan for an attack on a larger scale

Marx took the attack with equanimity. He regarded the native’s attack as understandable revenge for the labour traders who had earlier kidnapped some of his people: ‘their immutable law is a head for a head, what is worse they don’t care much whose head it is as long as they succeed in getting one, fortunately they were unsuccessful in getting mine·. Captain Clayton, sympathised with Marx but thought he should have been firmer in his reaction. As senior officer he followed up the incident:

Got into communication with the natives where they attacked Marx. They were very defiant and insolent and refused to give up the man and said they would fight us. This all comes because he did not promptly punish them, I fired a few shells to clear the bush of any lurking gentlemen and then sent Shakespear [1st.Lieut.] in to burn the small villaqe…., after much trouble he got on shore…and did all that was required, destroyed a few canoes and burnt a few houses, rather an inadequate punishment for trying to kill Marx but there was nothing else be done…

On another occasion, Clayton and his men marched a couple of miles along the beach to Chief Koapina’s village where, as Clayton wrote, ‘the square as usual adorned with skulls. I informed them that the Queen’s flag could not be hoisted where such emblems were displayed. The natives were scared to touch them for superstitious reasons so the teachers from another island tore them down. I promised them that the Queen would protect them if they led peaceful lives. The union Jack was hoisted, a round of ammunition fired, then three cheers and the chief was presented with a tomahawk ,an axe, some red cloth and tobacco.

It is worth noting that both Marx and Clayton were able to appreciate the good qualities of the natives. Both admired the dignified chief Koapina. Marx noted, ‘Caopina came in. He holds himself aloof from the other natives, is a fine man.’ They both understood only too well, the difficulties of keeping the peace on the station without undue severity.

The British public were less understanding. News was coming in of criticism levelled in Parliament and the press about the actions of warships in Australia. Articles were appearing in the press: ‘The Western Morning News says I have devastated and laid waste six of the fairest islands in the Pacific, which is beautiful talking, quite equal to the shrieks of the Daily Telegraph or Pall Mall…declared Clayton. The trouble rumbled on. Dr.Cameron took up the question in the House of Commons, as to ‘whether it was true that villages had been shelled and burned, nets and canoes destroyed, and coconut plantations laid to waste·

The First Lord had declined to comment until he knew the facts. An inquiry was ordered and papers printed in September of 1886, relative to ‘Armed Reprisals in the Western Pacific by Diamond, and other ships.’6 Captain Clayton kept assuring his wife that he was not really troubled. He told her that the Admiral had said, ‘there may be one or two small things that that I can’t positively say that I approve of but then I was not on the spot and cannot judge….I will back you up in everything’. In the event, there was no public censure by Admiralty reprimand but it is obvious that Clayton was made very anxious by this adverse publicity when he felt that he was only doing his duty to the best of his ability.

Another area of work which involved Clayton and Marx on the Australia station was the political and diplomatic. Tryon sent a private note to Marx asking for a description of Noumea and signs of any French activity in the area. When received, Marx’s report and sketch survey prompted the grateful thanks of both Tryon and Their Lordships. In 1886 Clayton’s orders were ‘to keep an eye on the Germans’. His orders were specific, visit Samoa from time to time ·anything of sufficient importance to report, return at speed to acquaint me.

The situation in Samoa was complicated. Suffice it to say that there were two opposing factions; the so-called King, Malietoa, who wanted the support of the English, and one led by the Vice King Tamasese, the rebel who was supported by Germany. German business interests in the area had drawn Bismark and Gladstone unwillingly into the fray and the Americans also were nosing about. Clayton found it difficult to tolerate ‘the Samoan squabbles…. Greenebaum (American ) is playing a double game and counselling Malietoa to fight. So poor Powell, the English consul had to go and rout the king out to checkmate him…I am tired of all this horrid duplicity and trickery… the Germans are playing a double game·, the only man acting fairly is Powell. ·the Samoans are all longing to be annexed to England.’ The Samoan tangle continued to enmesh British warships and their Captains until the division of the islands between Germany, Britain and America in the tripartite agreement of 1899. Then Clayton had to be off to the New Hebrides which ‘were making a noise in the world’ because the French were vying with the British to declare a protectorate interest in the area. In 1887, Tonga became the focus of trouble.

The problem here stemmed from the ambitions of the Prime Minister, an ex missionary, Mr.Shirley Baker. Baker, with the help of the King, George Tupalu, was trying to force all Tongans to be members of his Free Church, instead of Wesleyans. An attempt was made to shoot Baker. There were riots. The New Zealand times described the situation: ‘the Wesleyans were outlawed….college grounds invaded, men, women and children were thrashed and beaten in order to induce them to change their church. Many were left for dead.’ The paper pointed out the danger of French involvement, ‘a French man of war is expected to reach Tonga in a few days·.the French government want a coaling station between Tahiti and New Caledonia and there is now no doubt but that they have good cause for interference.’7 Mitchell, the High Commissioner and Tryon agonised over whether to send a British warship. Tryon was short of ships and there were demands for them on all sides. In the event Clayton was ordered to go to Fiji and pick up Mitchell, the High Commissioner and take him to Tonga for an official government inquiry. The finding was against Baker and the King and Baker later left the island.

At the end of the inquiry Clayton returned to Sydney and a new Admiral – Admiral Fairfax. But now there was a growing atmosphere of dissatisfaction in the fleet. There was no good, graving dock on the station, artificers and clerical staff were always short. Clayton complained of only having one ship’s doctor when there used to be two. He complained of a lack of lieutenants and difficulty in manning. There was much talk of a need to reinforce the squadron and Clayton wished he could update his knowledge of the modern Navy, ‘here everything is obsolete and out of date’.

The new Admiral accompanied Clayton on patrol. He attended various tribal gatherings and gave ‘severe wiggings’ where necessary. In remote parts off the Solomons, Clayton introduced him to the natives as, all same Queen of England’. In the incident of the burnt remains of a cutter stolen from Fiji The Admiral ordered the cutting down of over a hundred trees and they fired three shells into a village high on the mountain.’I am very glad the Admiral has seen one of these horrid expeditions.’

But it was not all doom and gloom. There was always the social life of the Station. The Royal Navy was a symbol of imperial prestige from which Australians derived both security and a sense of social importance beyond their own small confines. Royal Naval news was carried in the the society columns of the main newspapers and naval officers were in demand at all social events. For them it was a constant round of entertainment: balls, regattas, concerts, picnics and parties of all sorts. Warship visits were demanded by Hobart, Auckland, and other cities as a matter of prestige – a social epiphany on the outskirts of empire. But they were also a chance for the young colonial women of the colonial ‘fishing fleet’ to catch an eligible officer. Marx had tea with the Heaths and their three daughters in Brisbane, . ‘Mrs. H anxious to know whether I am engaged…’ Marx was evenutually ‘caught’ by Lily Heath. They were married in 1886. Clayton did not approve.

it is a great mistake for a young lieutenant to get married… no naval officer ought to marry till he is a commander in my opinion but it is hard now as lieutenants are not promoted till they are nearly 35 or evenmore.

Marx was 33.

Although colonial officers enjoyed the status conferred on them by the presence of the imperial Royal Navy, there was an increasing rivalry between naval and colonial government power and prestige. At the opening of the Adelaide Exhibition. in 1888, Clayton declared,

I have seen the Chief, there is a great squabble going on about precedence and it seems very possible that the captains won·t go at all on Wednesday if they don’t give us our proper place. Personally, I should be delighted but of course we have to fight these things for the sake of the service and as the Navy was very much ignored at the Sydney festivities we have to be on our guard this time.

Arguments about British and Colonial funding for naval defence exacerbated the situation.

Despite coming to the end of his commission, longing for news of his relief and his orders to sail home, in 1888, Clayton found himself in demand as senior officer on the station with orders for another trip to the islands, ‘I am to inaugurate the new Anglo French Commission …as hopeless a bit of international legislation as our imbeciles at the Foreign Office ever invented. I don’t speak French and have no one on board who does’….in fact, his French wasn’t bad’ The Commission consisted of Captain Clayton with his two lieutenants, Simpson and Williams, and Captain Benier of the Fabert with his Ensignes de Vaissaux, Legarde and Lavenir. The French Admiral, Lefevre was on hand to agree proposals. Clayton expected Fairfax to put in an appearance but he remained in Sydney. Fairfax was dismissive of the Commission and was more interested in Clayton bringing back a particularly interesting croton, or fern, from the New Hebrides. The provisions of the treaty were drawn up by simple discussion in ‘any amount of bad French and English’ on board Diamond. Basically, they provided for shared patrolling and jurisdiction of the area; provisions which despite legal difficulties provided a successful framework for dual control of the New Hebrides, thereafter.

Marx had left the Station in 1886. He had enjoyed the excitement and interest of working in an imperial environment as a junior officer with a considerable degree of automous responsibility. It led to his promotion as Commander in 1889. Clayton left in 1888, glad to be free of the onerous duties of a senior officer… Both men represented the best of the imperial Royal Navy. They were not without faults but they carried out their duties with competence and humanity in difficult circumstances. They were the role models for the subsequent, independent Australian Royal Navy established in 1913.

Appendices

British Navy Ships on Australia Station, 1885 – 89

| Ship | Date | Class | Complement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calliope | 1888-89 | Calypso class, steel screw corvette | 317 |

| Dart | 1882-1901 | Philomel class, wooden gun vessel | 60 |

| Diamond | 1881-88 | Amethyst class, wooden screw corvette | 225 |

| Espiegle | 1882-85 | Doterel class, composite screw sloop | 140/150 |

| Harrier | 1883-87 | Schooner | 20 |

| Lark | 1881-87 | Schooner | Unknown |

| Lizard | 1888-97 | Bramble class, composite gun boat | 76 |

| Miranda | 1880-86 | Doterel class, composite screw sloop | 140/150 |

| Myrmidon | 1888 | Cormorant class, wooden gun vessel | 90 |

| Nelson | 1881-1897 | Iron armoured cruiser | 484 |

| Opal | 1885-90 | Emerald class, composite screw corvette | 230 |

| Orlando | 1887-97 | Armoured cruiser | 484 |

| Rapid | 1886-97 | Satellite class, wooden screw corvette | 170/200 |

| Raven | 1883-90 | Banterer class, composite screw gunboat | 60 |

| Royalist | 1888-99 | Satellite class, wooden screw corvette | 170/200 |

| Swinger | 1884-91 | Ariel class, composite screw gunboat | 60 |

| Undine | 1883-87 | Schooner | Unknown |

Tonnage and Armament of British Navy Ships on the Australia Station 1885 – 1889

| Ship | Displacement Tonnage | Armament |

|---|---|---|

| Calliope | 2770 | 4-6in BL Mk IV, 12- 5in BL MK 11, 10 MGs, 2 TCs |

| Dart | 570 | 1-110pdr BL, 2- 24pdr howitzers, 2-20 pdr BL |

| Diamond | 1970 | 14 – 64pdr MLR |

| Espiegle | 1130 | 2-7in MLR, 4-64pdrMLR |

| Harrier | 190 | 5-18in TT, 2- 4.7in, 4-6pdr, I Nordenfeld 5-barelled MG |

| Lark | 166* | 1-12pdr Westacott |

| Lizard | 715 | 6 – 4in QF |

| Miranda | 1130 | 2- 7in MLR, 4- 64pdr MLR |

| Myrmidon | 877 | 1-110pdr, 1-68pdr SB. 2-20pdr, 1-7in MLR, 2 – 64pdr |

| Nelson | 7473 | 4-10 MLR, 8-9inMLR, 6 – 20 pdr |

| Opal | 2120 | 12-64pdr MLR |

| Orlando | 5600 | 2-9.2in, 10- 6in BL. 6- 6pdr QF, 10- 3pdr QF , 6-18in TT |

| Rapid | 11420 | 6-32pdr ML SB, 4-30pdr Armstrong BL , 1-40pdr Armstrong |

| Raven | 465 | 2-64pdr MLR, 2-20pdr BL |

| Royalist | 8-6in BL. 4- MGs, 1 light gun | |

| Swinger | 430 | 2-64pdr, 2-20pdr |

| Undine | 280 |

* Builders Measurement Tonnage

References

- PRO, ADM2/1697, 18.2.1854 , secret orders Admiralty to Freemantle.

- W.P.Morell, Britain in the Pacific Islands , p.185

- Report of a Commisson appointed to inquire into the working of the Western Pacific Orders in Council and the nature of the measures requisite to secure the attainment of the objects for which these orders in council were issued. ( BPP , 1884, LV.871)

- ADM 122/5., 11.11.86, Admiralty to Tryon

- Clayton’s letter to wife, 1.8.1886

- BPP, 1886, XLI , 425

- ADM 1/6866, 23.2.87 New Zealand Times

For further details of Captain Clayton and the Australian Station, see Mary Cross (now Jones) , ‘Captain Clayton and the Australia Station , 1885-1888′ (unpublished master’s thesis , University of Exeter , 1994) and “Pretty little Hobart” : Captain Clayton in Tasmania from 1885- 1888’, Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Papers and Proceedings 41(3) Sept. 1994. Also see article on Captain Clayton in The Naval Miscellany . Volume V1, Navy Records Society, 2003

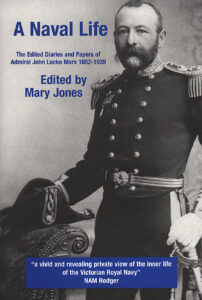

For details of John Locke Marx see Mary Jones, A Naval Life, Persona Press, 2007